What are fungi

By Claudio Scazzocchio

Visiting Professor, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Departament of Life Sciences, Imperial College London and

Prof Emérite, Institut de Biologie Intégrative de la Cellule, Université Paris-Saclay

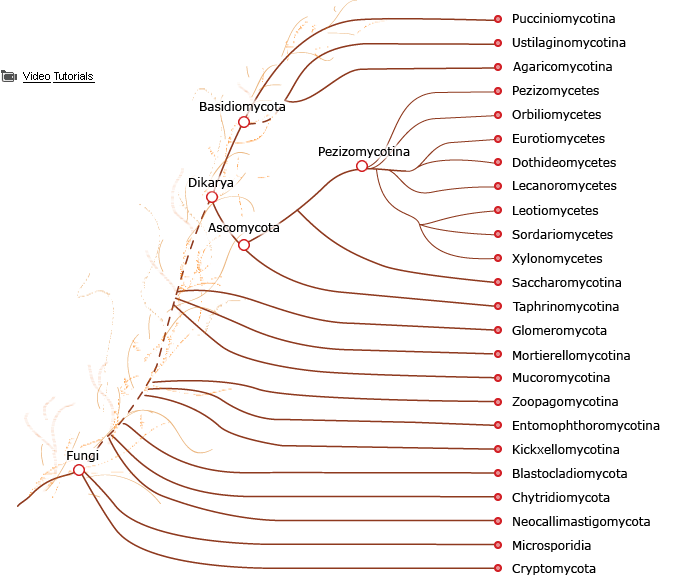

I should rather ask a different question. Or better still, two related ones. What organisms we deal with at the European Conferences in Fungal Genetics? And do we deal only with Genetics? The answers to these questions are somewhat opposite. The answer to the first question is restrictive. As organisms, we deal with all fungi except “yeasts”. And this raises two other questions. What are yeasts? and Why the exclusion? Yeast is not a taxonomical but a descriptive term. It designs fungi that are single celled and not mycelial. Thus, there are ascomycete yeasts (such Saccharomyces cerevisiæ, Saccharomycotina, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Taphrinomycotina) and basidiomycete yeasts (such as the pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans). The EFGCs include every fungus except ascomycete yeasts. It used to be said that we dealt with “filamentous fungi”, which is another way of spelling this exclusion. The reasons for this exclusion are not scientific but historical and sociological. The “yeast” research community is huge. They hold their own general and also specialised meetings. The International Conferences on Yeast Genetics and Molecular Biology attract about 1000 participants. Searching Saccharomyces cerevisiæ leads to >140.000 entries. Searching Neurospora crassa to somewhat less than 8000. Searching Ustilago maydis to slightly over 1000. This unbalance lead to the unfortunate segregation of two different research communities, the “yeast ones” and everyone else, which rarely coincide in specialised thematic meetings. Two “everyone else” meetings developed. One in the USA, is an offshoot of the specialised Neurospora conference that burst into the Asilomar Fungal Genetics Conference, the second is the European Fungal Genetics Conference, which developed after a series of EMBO sponsored workshops. These two events take place in alternative years and are complementary. They both exclude “yeasts” but include in some instances work on organisms that are phylogenetically unrelated to fungi but show a “fungal-like growth” such as Oomycetes. The answer to the second question is more inclusive. While both meetings were started by people that were geneticists and whose intellectual quests were guided by genetics, today we deal with most aspects of fungal biology.

With this proviso, I should go to the conceptual question: What are fungi? In my life time, and about half a century ago, fungi were considered “plants” and were taught in the Botany classes even together with bacteria (!). They were included together with algae, mosses and ferns in the “cryptogams” (seedless plants) as opposed to the Phanerogams (plants with seed, flowering plants). The “Barker Chair of “Cryptogamic botany” in the University of Manchester was first occupied by a Bryologist (1909-1940) and was last occupied by a fungal biologist (who we could call Mycologist, 1981-2001) even if by 1981, we had (not for long) known that fungi were not “plants”. The identification of fungi as “plants” stems from classical antiquity but was systematised in the XVIII century by naturalists including Pier Antonio Micheli, the “father of mycology” who first described Aspergillus, Botrytis and Mucor species.

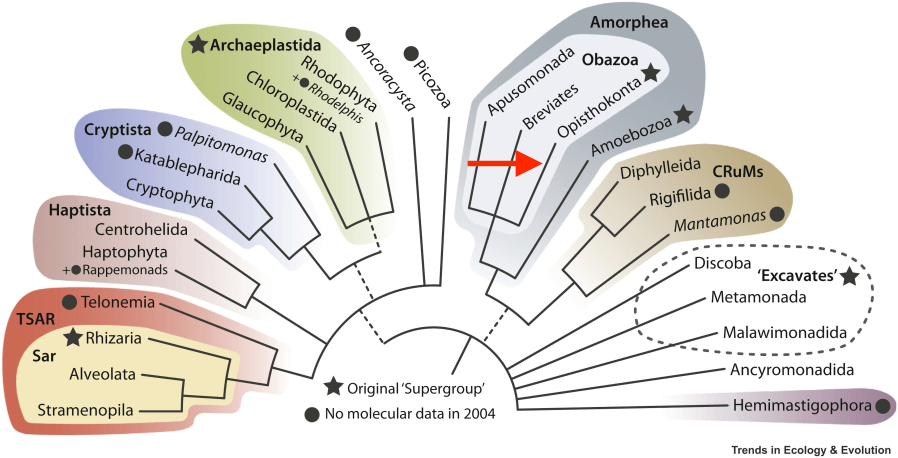

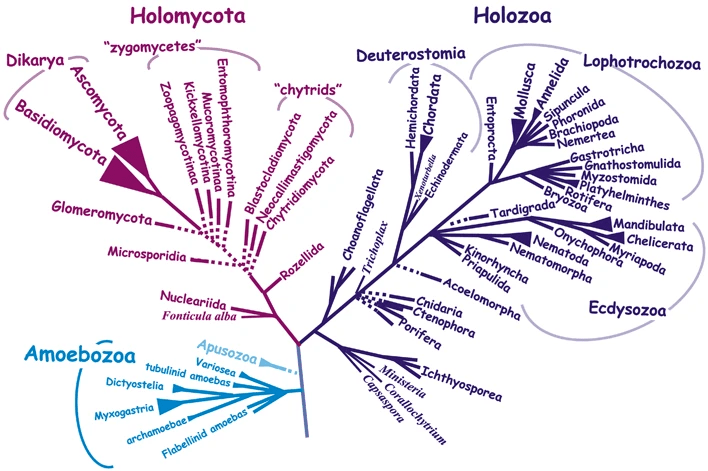

The separation of fungi from “plants” occurred slowly and gradually in the XXth century. First, fungi were incorporated into the very heterogenous group of “protista”, and more importantly were considered as “not plants” . The closer relationship between fungi and animals compared to plants was first proposed using ultrastructural (flattened mitochondrial cristae), biochemical (carbon storage as glycogen rather than starch, chitin as extracellular structural macromolecule) and genetic code characteristics (UGA codes for tryptophan, not stop in both animal and fungal mitochondria). In 1988, Cavalier-Smith proposed the taxon Opisthokonta to include animals, fungi and “choanozoans”. The basis of this grouping was that these organisms possess a posterior unique flagellum (more exactly a cilium, the name means a “posterior pole”) at some stage of their development. For animals, these would be the cilium of the sperm, while for fungi motile, ciliate forms are to be found only in basal taxa as motile zoospores (Blastocladiomycota, Chytridiomycota and Neocallimastigomycota, Olpidiuml-Rozella complex). The close relationship between fungi and animals was also supported by phylogenetic studies using ribosomal sub-units and EF-1α translation elongation factor sequences. In addition, a 11 amino-acids insertion in the sequence of EF-1α was conserved among fungi and animals, including microsporidia. Several other protein sequences confirmed this phylogenetic relationship. In 2005, the classification of Eukaryotic organisms definitively included the Opisthokonta clade and it was further supported by whole genome sequencing of many organisms.

Fabien Burki, Andrew J. Roger, Matthew W. Brown et Alastair G.B. Simpson, « The New Tree of Eukaryotes », Trends in Ecology & Evolution, vol. 35, no 1, janvier 2020, p. 43-55 (ISSN0169-5347, DOI10.1016/j.tree.2019.08.008

Recent phylogenomic studies showed that the zoosporic plant parasite Olpidium bornovanus is the sister species of all non-zoosporic “higher fungi”. Within opisthokonts, two major groups were identified, holozoan gathering animals and their nearest unicellular relatives and holomycota which includes all fungi and, as sister groups, nucleariids and the “slime mold’ Amoebozoa Fonticula. This is an interesting example of convergent evolution, as “slime molds” are definitely not opisthokontans. Overall, fungi are a major eukaryotic taxon usually call as a kingdom which comprises a few million species of varied morphologies, life cycles and ecologies. They are the major sister groups to the kingdom “animals”, which explains their model status in the study of multiple problems of cell biology shared with animals. Despite their diversity, genetic and physiological studies were, as in other kingdoms, mainly developed using a limited number of model organisms including important industrial microbes an well as devastating human and plant pathogens.

Right: The lineages of Opisthokonta in. the Eukaryotic tree, from Baldauf, Romeralo and Carr, Evolution from The Galapagos, Two Centuries after Darwin, Chapter 7, The Evolutionary origin of Animals and Fungi; Springer 2013.

The Department of Energy (DOE) Joint Genome Institute (JGI) is a national user facility with massive-scale DNA sequencing and analysis capabilities dedicated to advancing genomics for bioenergy and environmental applications. Beyond generating tens of trillions of DNA bases annually, the Institute develops and maintains data management systems and specialized analytical capabilities to manage and interpret complex genomic data sets, and to enable an expanding community of users around the world to analyze these data in different contexts over the web. The JGI Genome Portal (http://genome.jgi.doe.gov) provides a unified access point to all JGI genomic databases and analytical tools. A user can find all DOE JGI sequencing projects and their status, search for and download assemblies and annotations of sequenced genomes, and interactively explore those genomes and compare them with other sequenced microbes, fungi, plants or metagenomes using specialized systems tailored to each particular class of organisms. We describe here the general organization of the Genome Portal and the most recent addition, MycoCosm (http://jgi.doe.gov/fungi), a new integrated fungal genomics resource.

Grigoriev IV, Nikitin R, Haridas S, Kuo A, Ohm R, Otillar R, Riley R, Salamov A, Zhao X, Korzeniewski F, Smirnova T, Nordberg H, Dubchak I, Shabalov I. (2014) MycoCosm portal: gearing up for 1000 fungal genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 42(1):D699-704.