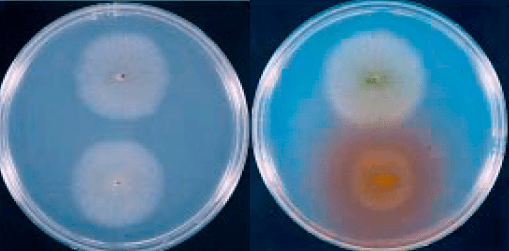

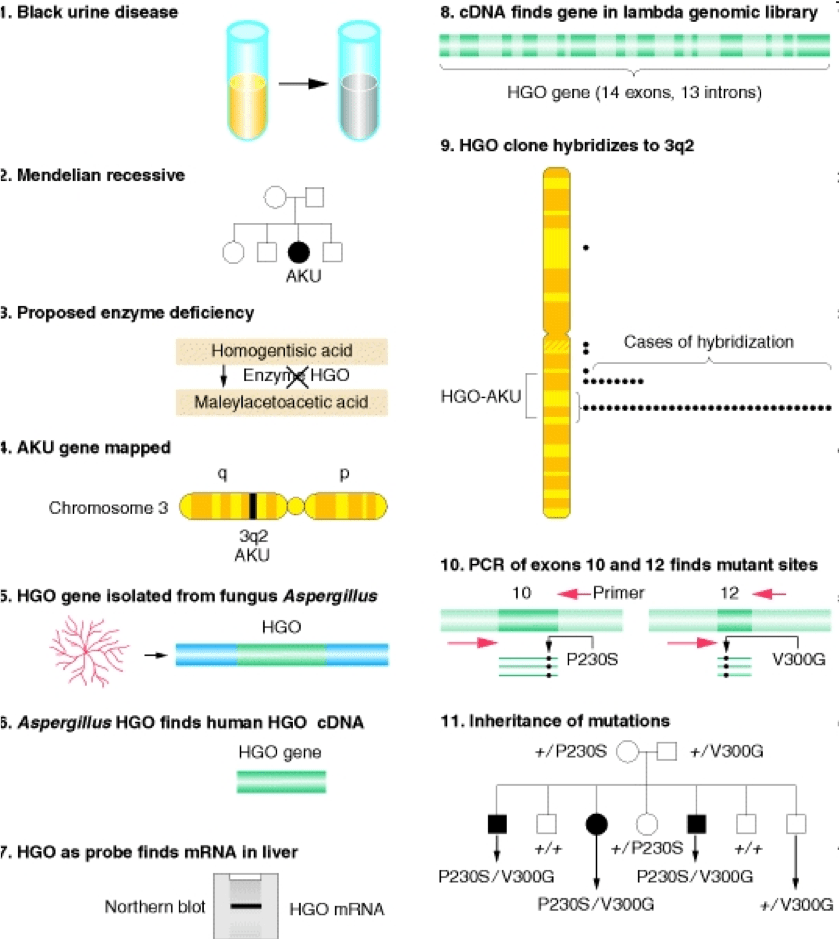

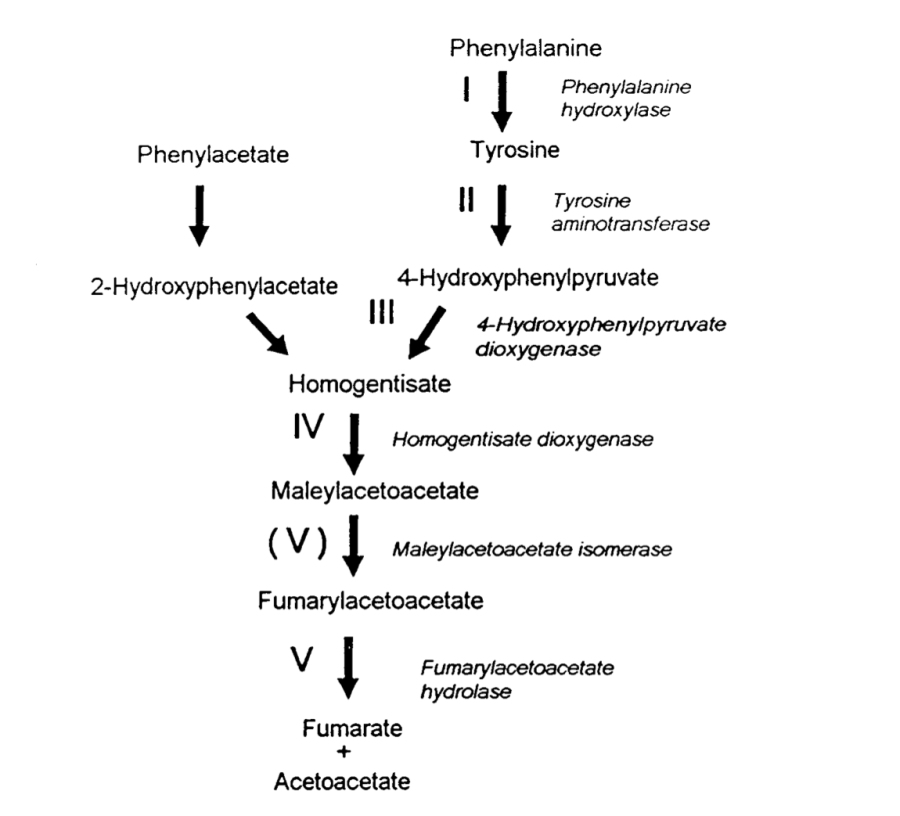

By 1994, the human genome project was in its cradle, and many genes involved in disease remain to be identified. Amongst them was the gene for alkaptonuria (AKU), the prototypic Garrod’s inborn error of metabolism. AKU results from deficiency of homogentisate deoxygenase (HGO), one of the key enzymes in the phenylalanine degradation pathway. AKU Behaves as a Mendelian-recessive character. While the disease is very rare (one child every 250,000 births) the consequences are severely debilitating, as the substrate of the deficient reaction accumulates in the connective tissue of large joints causing a progressive degeneration that, until very recently, was rather difficult if not impossible to stop. By 1993, Chema, a postdoc in my lab, was working out the pathways of degradation of phenylacetate using substractive cDNA hybridisation. The most frequent clone that he pulled out from the library encoded fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase (FAAH), which is precisely the gene acting downstream of HGO. Chema knocked out the gene and demonstrated that the mutant strain accumulated the same intermediates accumulating in human patients with type I tyrosinemia, a very severe and often lethal disease, nicely demonstrating the strong conservation of this degradation pathway across evolution. These findings led strong support to our view that filamentous fungi and Aspergillus in particular resembles metabolically the catabolic abilities of human liver. They also represented a strong source of motivation to get involved in the race to clone the gene. Aspergillus strains deficient in FAAH accumulated highly toxic compounds when exposed to phenylalanine or tyrosine, which resulted in inability to grow no matter whether or not other carbon sources were present in the medium. We soon realised that this conditional lethality could be used to select mutations in the gene encoding HGO. Given the fact that AKU patients didn’t seem to accumulate any toxic intermediaries, it was possible that, in a FAAH deletion strain, blocking the pathway upstream by knocking out HGO could prevent toxicity, thereby providing a powerful selective procedure. We didn’t need to wait for a second experiment, as the first mutagenesis that we carried out was impressively reassuring. We obtained literally hundreds of strains that, unlike the parental FAAH deletion strain, were able to grow on a mixture of lactose and phenylalanine. Notably, these strains accumulated, upon prolonged incubation, a dark brown pigment that resembled the ochronotic pigment present in the urine and joints of AKU patients. both Chema and I were fully convinced that our mutagenesis had hit the AKU gene (fungal). The only thing that was still needed was demonstrating it. Once more, fungal genetics came to help. I had been educated, during my stays in Claudio Scazzocchio’s lab, that genes belonging to the same catabolic pathway were often clustered into the genome. back-crossing the double mutant strains resulting from the mutagenesis revealed that the lethality-rescuing mutations mapped at less than one cM from FAAH, indicating that both genes were clustered. That made the cloning of the gene trivial, as all we had to do was looking for cDNAs proceeding from regions neighboring the FAAH gene. A set of these cDNAs encoded a protein with certain features of a dioxygenase enzyme. We purified the protein from recombinant bacteria and demonstrated that it had a very strong activity of homogentisate dioxygenase. Now we were positive that we had isolated and identified the HGO gene. At that time of the human genome project, some of the relevant libraries that were available were going to be very useful. These were the libraries of expressed sequences tags (abbreviated ESTs). These tags were small bits of cDNAs that had been randomly sequenced, and that, by conceptual reverse translation, permitted the identification of the corresponding protein. As we had predicted, the human and fungal amino acid protein sequences were markedly similar, and BLASTP screening of human reverse-translated ESTs with the Aspergillus HGO sequence identified bits of amino acid sequence of human HGO. Repeated blasting of these databases with incomplete cDNAs which partially overlapped, allowed us to fully reconstruct in silico a complete cDNA for HGO. We were very short distance from determining the molecular basis of alkaptonuria. but this distance was equally as steep as short, and we would have not arrived in due course wouldn’t it have been for the crucial implication of my colleague and bicycling friend Santiago Rodríguez de Córdoba, by the way an outstanding human geneticist. Santiago and I had arrived to the CIB at the same time, and had shared a laboratory for quite some time. Sitting on the steps of the fire staircase that connected my laboratory, at the fourth floor of the building, with his, at the basement, I proposed him to collaborate on the characterisation of the human gene and it took him less than five seconds to answer “yes, indeed”. And indeed he did, as he put all his weaponry at the service of the cause. But this will be the subject of another post. See you soon.

Page taken from Griffiths et al., An Introduction to Genetic Analysis, Seventh Edition, Freeman and Co. New York, 2002

The alkaptonuric fungus happily growing on the bottom right on a mixture of lactose and phenylalanine; the red pigment excreted by the colony is pure homogentisic acid, due to the genetic block labeled as IV on the above scheme. With time, The red color turns into deep brown due to the formation of polyquinones, which in medical practice are known as the ochronotic pigment.